Read Thomas Gomersall’s article to learn more about this year’s Earth Day theme ‘putting an end to plastic pollution’.

Islands of Hope in a Sea of Plastic

By Thomas Gomersall

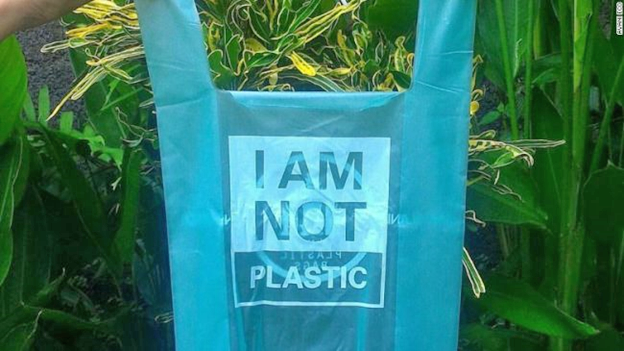

Source: https://www.livekindly.co/edible-biodegradable-bag/

There is no denying that plastic pollution is a serious environmental problem. One of the biggest of our time. More than eight million tons of plastic finds its way into the ocean every year. It is responsible for the deaths of countless marine animals, either through blocking their digestive tracts leading to starvation, or entanglement leading to drowning. On social media, YouTube and even regular internet ads, we see images of seas and beaches choked with mile upon mile of plastic, usually accompanied by the oft repeated statistic that there will be more of it in the sea than fish by 2050. We have to cut our plastic usage urgently and yet, as anyone who’s been into a supermarket can tell you, plastic is everywhere in our lives. We use it to package our food, to carry our shopping, even to drink out of. Much of the plastic polluting the environment now is disposable items that, try as we might, we can’t yet seem to fully sever our ties to.

Amidst all of this negativity, it’s easy to become cynical. To think that this problem is insurmountable. To assume that humanity will acknowledge the threat of plastic pollution, but ultimately sit on its hands and do nothing about it. But actually, in spite of our addiction to disposable bottles and shopping bags, there are many reasons to be optimistic. Here are a few of them:

- Governments are actually doing something about it

When it comes to any sort of positive change, especially with regards to the environment, many of us have come to expect very little of politicians. But when it comes to plastic pollution, for once the world’s governments are putting their money where their mouths are. Just this week, UK Prime Minister Theresa May proposed a ban on plastic straws and cotton buds. The latest in a string of measures Britain has taken to curb plastic pollution including a 5p charge on plastic shopping bags (leading to a 30% decrease in British sea beds), a ban on microbeads in cosmetics and plans for a plastic bottle deposit scheme the likes of which has been found to increase recycling rates to 98%. The UK is far from alone in this fight. France has also banned microbeads having already outright banned plastic shopping bags and passed a law that all disposable cutlery, cups and plates must be made from biodegradable materials by 2020. Meanwhile, Belgium plans to ban microbeads by the end of 2019. These efforts are not limited to wealthy countries either. Last year, Kenya not only joined a growing list of African countries banning plastic bags, but also imposed severe fines and four year prison sentences for the manufacture, sale or possession of new bags while confiscating existing ones. Costa Rica is being even more ambitious, with plans to be free of disposable plastics by 2021.

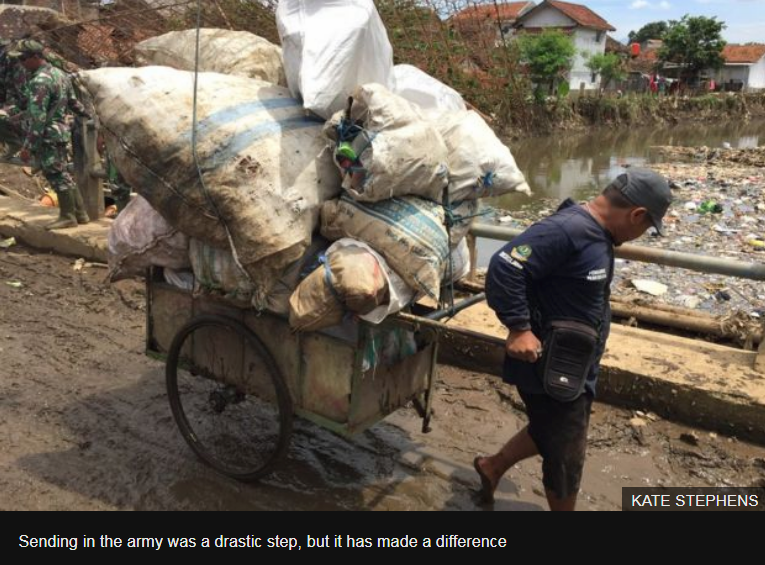

Even governments in Asia, which produces 86% of the world’s plastic waste, are taking the first tentative steps towards curbing it. India recently introduced a ban on disposable plastics in its capital city, New Delhi, and half of all Indian states have imposed bans on plastic shopping bags, albeit with a so far limited impact. Efforts have been more successful in Indonesia (one of the top 5 Asian polluters), where a tax on plastic bags has led to a big reduction in their use. In late 2017, mainland China sent shockwaves around the world when it introduced a regulation to no longer allow foreign plastic waste imports into the country. While it’s unclear what effects this will have on China’s domestic pollution levels, many have predicted that this will force Western countries (for whom China was the biggest recipient of their plastic waste) to drastically improve their own waste management tactics and facilities to avoid an impending litter build-up.

- So is everyone else

Thanks in no small part to documentaries like Netflix’s ‘A Plastic Ocean’ and, more recently, the BBC’s ‘Blue Planet II’, public awareness of plastic pollution has grown significantly. The growing support for reductions in plastic use has subsequently led many businesses to commit to phasing it out from their products. In the UK, both McDonalds and supermarket chain Tescos have committed to no longer provide plastic straws by as early as this May, as have a growing number of restaurant and food outlets in London. And straws aren’t the only plastic that businesses are looking to rid themselves of. At the World Economic Forum in Davos this year, 11 major companies including M&S, Coca-Cola and Walmart were revealed to be committing to having all the packaging for their products be 100% recyclable or biodegradable by 2025 at the latest.

But big corporations aren’t the only ones taking responsibility. Ordinary people are helping to organise beach cleanups and some have even turned it into a business. Last year two American surfers realised that fishing nets would be a perfect tool for plastic removal watching fishermen in Bali struggling to get their boats through a barrier of it. To create an economic incentive for this, back home they started paying a local sea captain to fish rubbish from the sea, leading to the establishment of 4Ocean. This company sells bracelets made from recycled plastics and every bracelet sold pays for a pound of plastic to be removed from the sea. In just over a year, 4Ocean has set up operations in 3 countries, employed seven captains on a full time basis and have collected over 250,000 pounds of plastic.

A twenty three year old Dutch entrepreneur is taking this idea of fishing for plastic a step further. Realising the impossibly huge levels of manpower and money needed to manually clean up the ‘plastic island’ of the central North Pacific, Boyan Slat has proposed letting the sea do the work instead. Plastic islands form in the centre and edges of gyres, vast areas of calm water surrounded by circular currents. Slat’s proposal is to install a series of giant boons connected by nets in these currents, allowing any plastics they carry to be caught in the nets to be collected later. Although initially considered unfeasible, this invention has already been successfully tested in the North Sea and is due to be transferred to the North Pacific gyre this year, where it is expected to catch 50% of the plastic currently floating in there. If successful, Slat hopes to repeat this experiment on other plastic islands around the world.

- Alternatives

For all the good that cleanups do, it still begs the question, what to do with all of this plastic? And what do we do about all the products we use in our daily lives that currently require plastic packaging? To which there are two possible answers.

The first is to recycle it. But not to simply wash out an old bottle and re-use it as a bottle, but to turn it into something far more long lasting and useful. For instance, in some areas of India and the UK, plastic bags and bottles are converted into tiny pellets and mixed with asphalt as a binding agent when laying roads. Not only is this a long term use for recycled plastic, but the plastic pellets have been found to be stronger than the traditional binding element, bitumen, meaning that the resulting roads need not be serviced so frequently. Good news for anyone who’s ever been frustrated by roadworks induced traffic jams. Furthermore, a recent, accidental discovery means that even the most hard-to-recycle plastics could find new life. In 2016, scientists discovered a new strain of bacterium in a Japanese dump that was able to break down plastics into polymers, allowing them to be reconstituted into new plastic. Then this year, attempts to study the evolution of the enzyme responsible for this unwittingly increased its efficiency, allowing it to completely break down plastic in a matter of days instead of the millennia it would take to happen naturally. The researchers are optimistic that the efficiency of this process can be increased further. If this bacteria could be harnessed on an industrial scale it would significantly increase plastic recycling, although at this stage, that is unlikely to happen.

The second possible solution is a substitute. Most of us probably know about metal drinking bottles but several restaurants have also started offering metal or paper straws. Biodegradable, even –in theory at least– edible plastic substitutes are also in the works. While none of them are on the market just yet, it could be that in a few years we will be using shopping bags and coffee cup lids made from plants, replacing the oil based polymers found in today’s plastic with those found starchy crops such as corn or potatoes. Or perhaps drinking from a plastic bottle made from mixing sugar and carbon dioxide at low pressures and at room temperature? Yes, that too exists. And with Theresa May announcing an increase in government funding for research into plastic alternatives, in the UK at least, many more could be about to follow.

Yung Yau College students collecting waste at Tulap Turtle Beach

Yung Yau College students collecting waste at Tulap Turtle Beach

Sources:

- 4Ocean: https://4ocean.com/pages/our-story

- Asian Correspondent: https://asiancorrespondent.com/2018/03/how-are-asian-countries-tackling-plastic-pollution/#UhaQzyT5hMYM83Gs.97

- BBC News: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-41069853

- BBC News: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-438172

- BBC News: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-42973529

- Fast Company: https://www.fastcompany.com/40419899/boy-genius-boyan-slats-giant-ocean-cleanup-machine-is-real

- Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/apr/16/scientists-accidentally-create-mutant-enzyme-that-eats-plastic-bottles

- Greenpeace: http://www.greenpeace.org/eastasia/press/releases/toxics/2017/Chinas-ban-on-imports-of-24-types-of-waste-is-a-wake-up-call-to-the-world—Greenpeace/

- Independent: https://www.independent.co.uk/environment/plastic-bottles-waste-recycling-pollution-single-use-keep-britain-tidy-water-a8307591.html

- NewPlasticsEconomy: https://newplasticseconomy.org/news/11-companies-commit-to-100-reusable-recyclable-or-compostable-packaging-by-2025

- Positive News: https://www.positive.news/2017/environment/29987/uk-to-introduce-worlds-strongest-ban-on-plastic-microbeads/

- Positive News: https://www.positive.news/2018/environment/32234/drop-in-plastic-bags-in-britains-seas-linked-to-5p-charge/

- Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-environment-plastic/despite-state-level-bans-plastic-bags-still-suffocate-indias-cities-idUSKCN1GA0IQ

- Sky News: https://news.sky.com/story/plastic-bottles-and-bags-recycled-to-build-roads-11101612

- Telegraph: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/03/28/mcdonalds-says-will-phase-plastic-straws-uk-restaurants/

- Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2016/09/19/france-bans-plastic-plates-and-cutlery/?utm_term=.5dc7e833e0a8\

- World Economic Forum: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/08/costa-rica-plastic-ban-2021/

- World Economic Forum: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/10/scientists-have-made-biodegradable-plastic-from-sugar-and-carbon-dioxide/

Leave a Reply